The divider

A story of growing up

The story below is my submission to the STSC Symposium, a monthly set-theme collaboration between STSC writers. The topic today is “Beginnings”.

“And don’t forget to use the divider,” the older lady behind the mahogany desk tells you, as she hands you a long sturdy piece of brown plastic, which looks like a ruler without the length markings. The words she says are simple but the way she utters them isn’t. You can hear distrust, mild annoyance, and a hint of pleasure derived from being in a position of power over you. It is years before people start calling this sort of tone and demeanor Soviet. Most of your teachers—even those whose pet you are—use this tone with you, and although you find it unpleasant, it does not surprise you one bit.

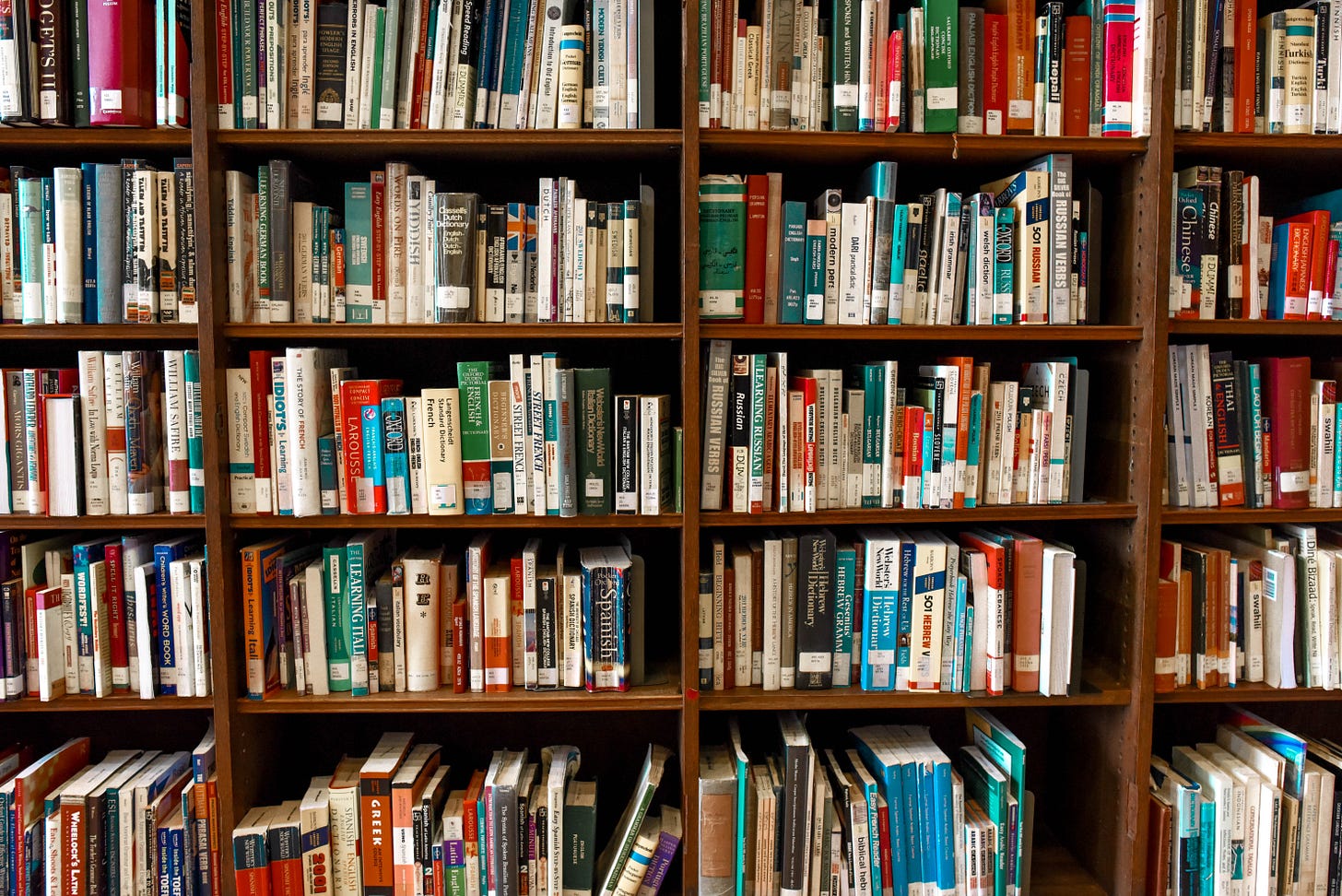

Clenching the divider in your hand, you start wandering aimlessly between the shelves, not even looking at the spines, just trying to escape the woman’s gaze. One would think that it should be easy in a place like this – the adult section of the library, where you had to write a request to get a card. The stacks are taller than you, the aisles are narrow, and there’s barely a gap between the books. Yet, in the dead silence of the place, you hear the librarian walk this labyrinth like a Minotaur out to get you. It’s hard to get lost in thought when you’re trying to lose a tail.

“The fiction section is at the back,” she whispers rather loudly, before disappearing in search of other interlopers and offenders. There are no reading desks in this hall, yet the golden rule of silence is observed at all times. When you come back here with a friend next week, she’ll kick you out for giggling at funny surnames like Vodkin. But you don’t know that yet. You hope to find something worthwhile after growing out of the outdated encyclopedias and Jules Verne novels that the kids’ section carries in abundance. You also hope that here you won’t be expected to glue the loose pages back.

There are only a couple of people browsing the stacks, looking for something to catch their eye. Unlike you, most visitors have a clear idea of what is it that they want. They have titles written down in their little notepads in the kind of neat yet inscrutable adult cursive that resembles the Arabic abjad more than it does Latin or Cyrillic scripts. They hand their notes to the librarian, who checks the titles against index cards she draws from a filing cabinet that takes up an entire wall. There’s no chit-chat or pleasantries involved, no recommendations are asked or given. The librarian herself might not even be a reader, just a person who likes order. And the divider you have been given is one of the tools that ensure this order.

The divider is there to curb agents of chaos like yourself from ever doing the unspeakable – not returning a book to its place. In this alphabetised and categorised order, every book has its place, and this order is temporarily broken every time someone takes a book. And if a volume is misplaced, even within the same shelf, it might take years for it to be located again.

But you’re a dreamer, with little care for how the world at large, and the world of the library works. You take a book, Stephen King’s Cujo, and stick a finger in the resulting gap, as you try to figure out how to squeeze the divider in. You try to place it horizontally, but the space left by the paperback is too narrow, and the other books on the shelf don’t budge. You decide that you will just take the book home and read it, as you don’t want to listen to a talking-to. After twenty minutes of browsing, you end up with a tall stack of books that doesn’t tumble only because it’s your lucky day.

“The limit is three books,” the woman scolds you in another power move, as you carefully place the stack in front of her.

“So do I… take them back?” you ask timidly, even if you know the answer already. She shakes her head and orders you to pick the three books to take home. Cujo, which you’ll read and enjoy, Zamyatin’s We, which you won’t understand, and a book on Zoroastrianism, which you’ll lose and never return, stay on the desk, while the books you’ll never remember, are placed on top of a flimsy looking trolley. You exchange the divider for your library card, with three first entries written in blue ink. And even though you’ll only learn how to use the divider correctly in a few weeks, your rite of passage feels complete once you slam the heavy door behind you.

Well done! The use of second person put me right in that moment, right in that library.

Such a brilliant story, Oleg - a really great read!

I remember visiting Chartwell, Winston Churchill's house near Westerham, Kent, many years ago. In his study, with its floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, were some soft toys - a panda, a dog, just ordinary little stuffed animals - dotted here and there between the books. I thought these were great but incongruous, and asked the attendant guide why they were there. 'Those were from his grandchildren: Churchill used them to mark where he'd taken books out.' I thought that was a great idea for someone with so many books!